Functional Product Concepts

Flex

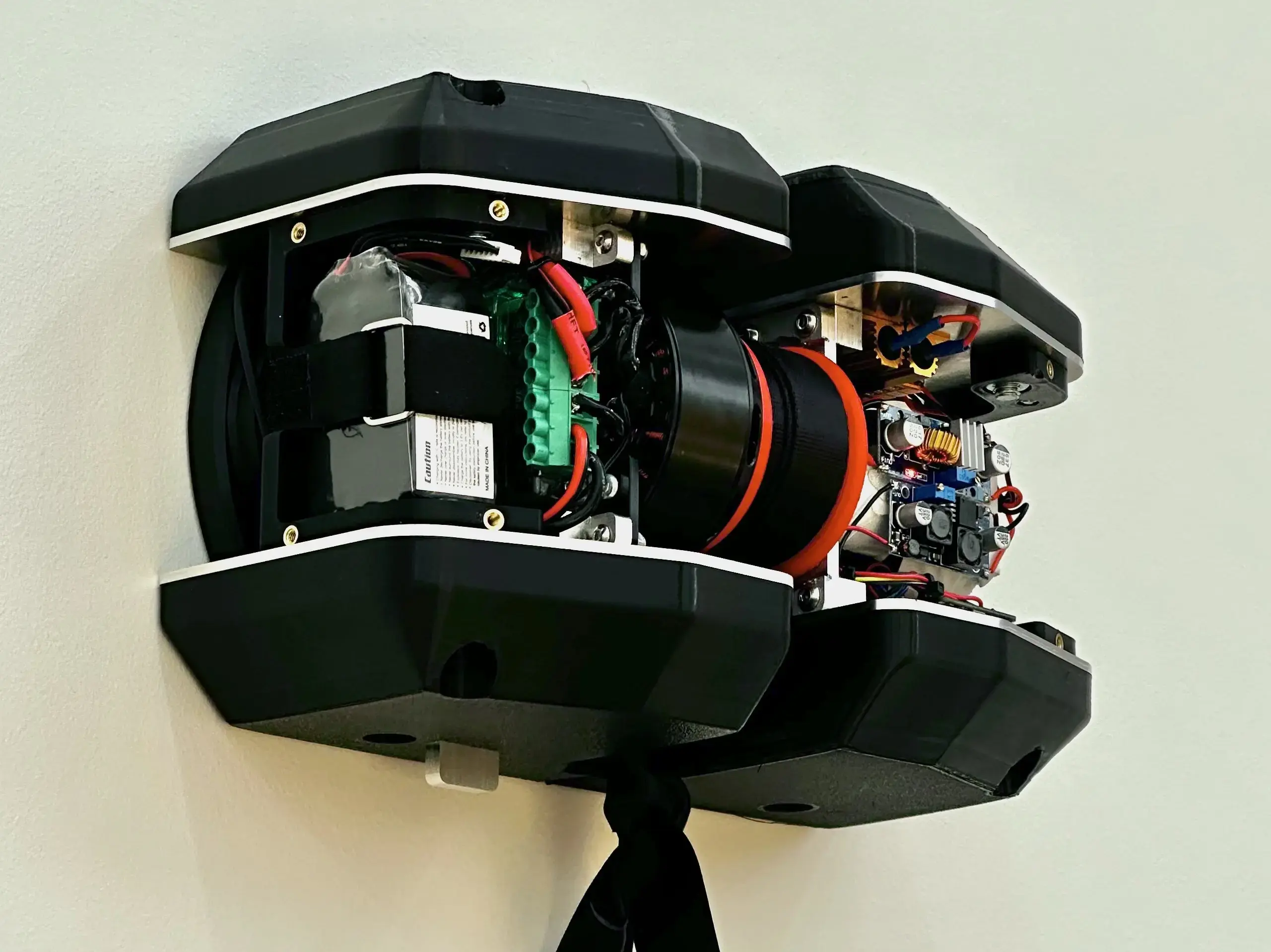

Flex prototype (outer casing removed)

Summary

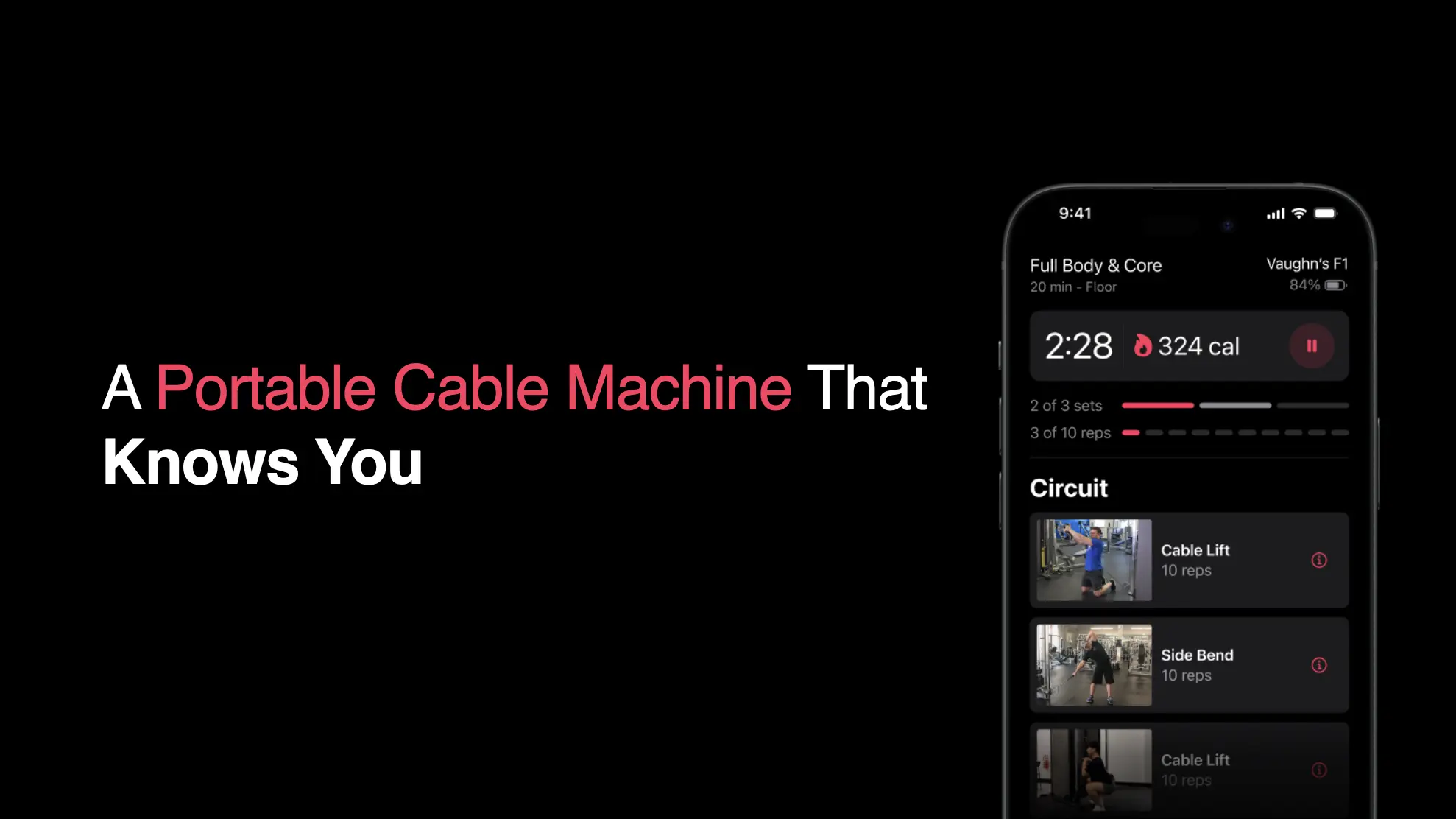

Flex was designed to be "Your gym, your trainer, anywhere." It's a cable workout machine that can generate as high as 45lbs of resistance with its in-built brushless motor.

As it resists pull, it also generates power—charging its internal battery—which means the device is fully contained and does not typically need to be charged. It's also capable of counting reps, quantifying percent load and effort scores, and connecting via Bluetooth to a trainer app with a social network where users can compete.

Instead of having a large frame, like a traditional cable machine, Flex uses your environment. Using a vacuum pump and rubber seal, it can attach to even rough surfaces like hardwood doors and flooring with enough strength to hold several hundred pounds. This enables workouts like squats, pull downs, OHTs, shoulder raises, and more—where the device is simply attached to your wall or floor.

I collaborated with two phenomenal team members to build Flex at a 7-week summer program in 2024. I was responsible for our prototype's hardware design, which was completed in Onshape, electronics built around a Raspberry Pi Pico, and firmware implemented in Micropython. At the end of the program, we pitched our concept to a board of executives with a live demo and keynote presentation.

Hardware & Electronics

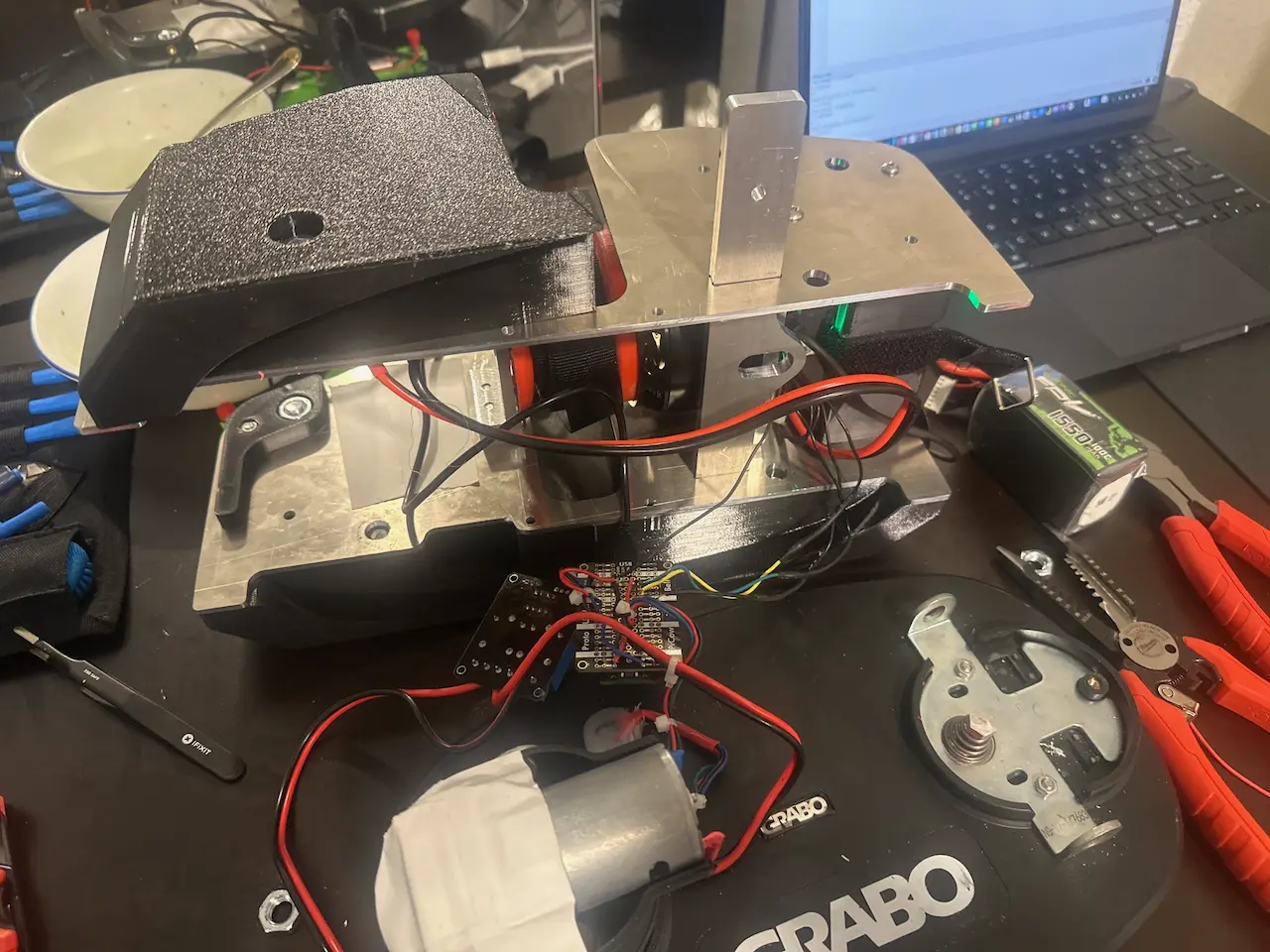

When we looked at the capabilities we wanted Flex to have, we knew that building it in 5 weeks would be a challenge. We took steps throughout the design process to make sure that our prototype would serve its purpose for our testing and live stage demo. At the same time, it was important to us that the final project looked polished and had a well-considered user experience.

The suction element of Flex meant safety was also a major concern, since the device would have to be aware of the pressure inside the seal, the force of the pull, and even the material it was attached to. All of this information would have to be processed in real-time to ensure that an unsafe scenario would result in the resistance motor being disabled—and this had to work without the app being connected.

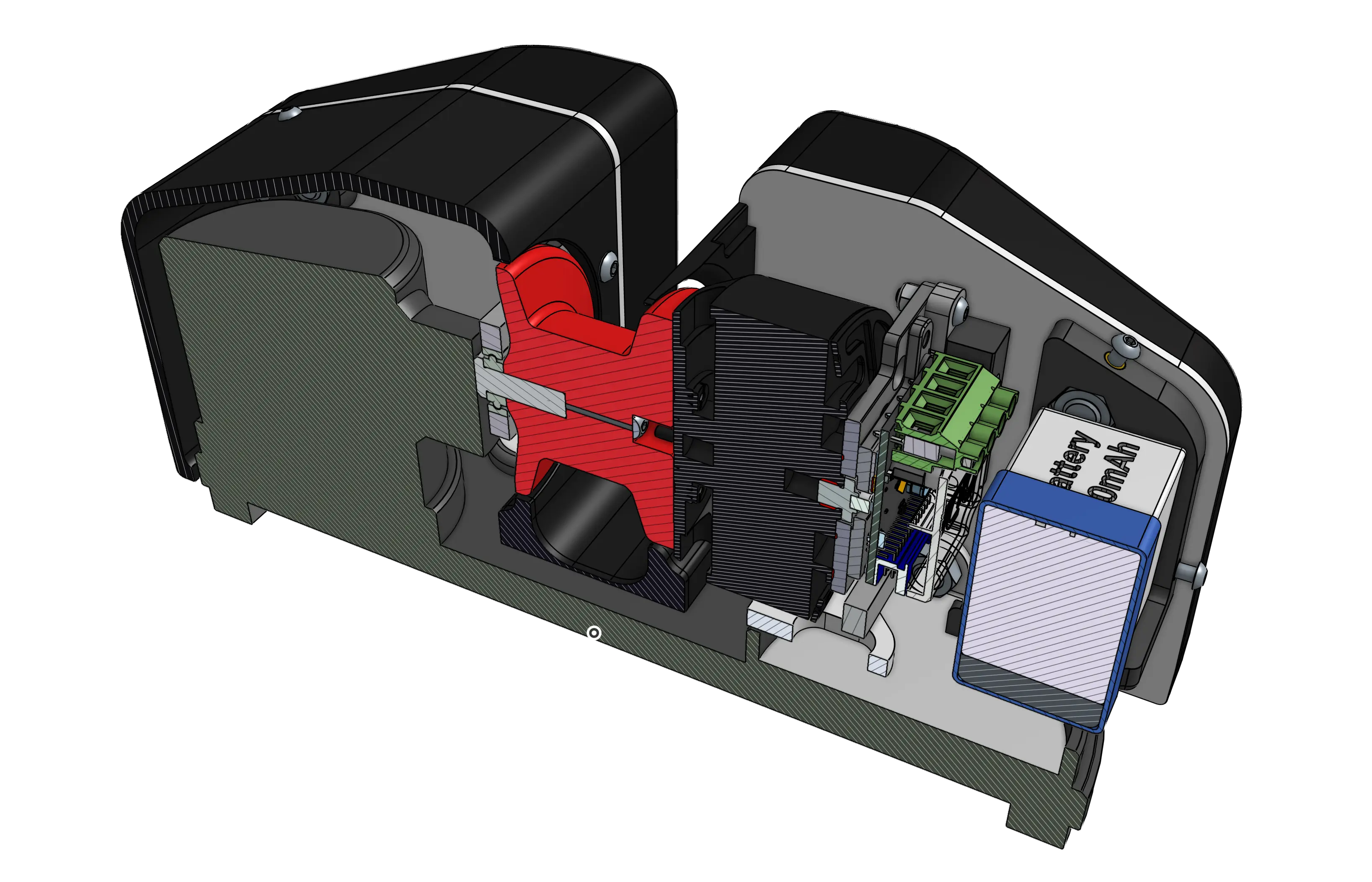

At its core, Flex is a heavily torn down GRABO suction lifting tool with a custom structure on top, built from 6061 aluminum plate and milled nut blocks. External TPU-printed shrouds ensure that the device is rugged and can survive some abuse. Internally, the resistance comes from a large 100KV brushless motor, controlled by an ODrive S1 and powered by a 6S 24v Lipo battery. The spool is printed from PLA and supported with a bearing on the side opposite the motor via an internally threaded shoulder bolt, ensuring that the internal motor bearings hold up.

To control all of the systems onboard Flex, a Raspberry Pi Pico is tucked in on the side opposite the ODrive S1, powered off the main battery via a 5v buck converter. The underside of the GRABO got two i2c-based sensors, a BME680 pressure sensor and a VL6180 IR ToF sensor, which are used to determine the suction strength and whether the device is on a surface. Wires for these sensors were fed through the base of the Grabo and then sealed with silicone.

All of the original power electronics were torn out of the GRABO, including the original battery, replaced by a 24>15v voltage stepdown wired through a digital relay. This relay enables digital control of the vacuum pump from the firmware. When combined with a removable PLA shroud and some custom-cut vinyl, the result is a fully-contained device that met our expectations for user experience, appearance, and polish. See the CAD here.

Firmware

The other major technical challenge I was responsible for while building Flex was the firmware, which I implemented in Micropython. This would have to handle all BLE communication with our app, controlling and reporting information from the ODrive controller over UART, reading values from the pressure and IR sensors via i2c, and ensuring that the device handles any error cases safely.

Micropython was used since it had full support for Bluetooth, but it lacked existing libraries for the pressure and IR ToF sensors (Adafruit only implements these in CircuitPython :/). That meant the first major hurdle was implementing custom libraries for these sensors based on their datasheets and CircuitPython implementations. Next, the boilerplate code for the Bluetooth communication was written, defining all of the Bluetooth addresses to be used and their characteristics.

Additionally, I wrote wrapper files for controlling the pump relay and interfacing with the ODrive over UART, abstracting away comms implementation and error handling. A GCode checksum was also implemented on the ODrive UART to ensure that signal integrity issues would not lead to erroneous commands being sent to the motor.

def read_bus_voltage(self):

self.uart.write("r vbus_voltage *93\\n")

time.sleep(0.01)

if self.uart.any():

response = self.uart.read()

try:

voltage_str = response.decode().strip().split('*')[0]

return float(voltage_str)

except ValueError:

print("Error: Invalid voltage value received.")

return 0

return -1

Example function in motor_control.py (*93 is the GCode sum)

At the top level, the main Flex functionality was implemented as a state machine. The state was a read-write Bluetooth address, meaning that it would tell the app the current status of the hardware, and the app could also reset the state manually (to escape an error case) or advance it to initiate a workout. Other write-only and read-only addresses set the ODrive torque cutoff (effectively the weight), and allowed the app to log critical data like power output and battery voltage. Read the full state machine code on the Github here.

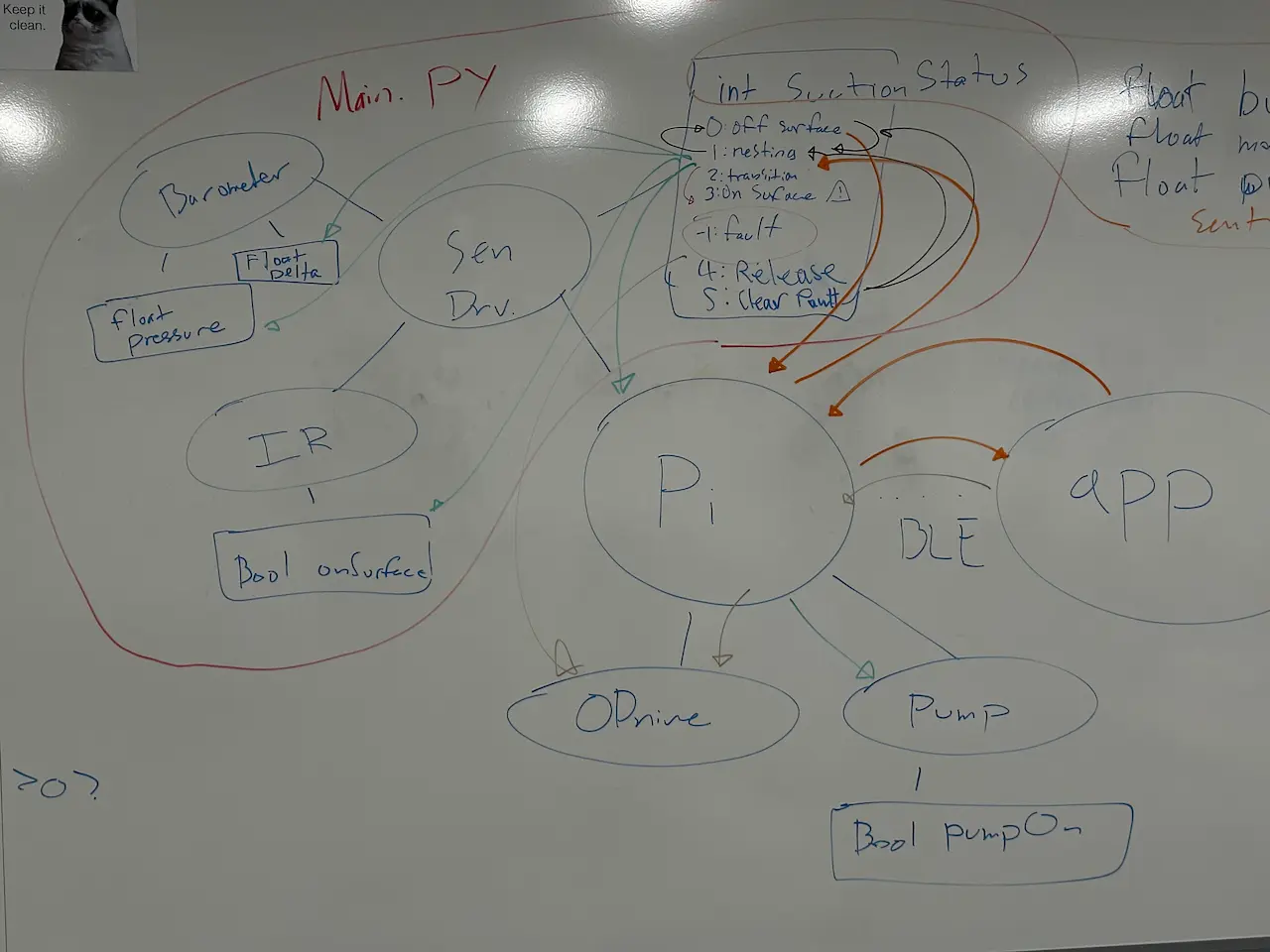

Early whiteboarding of state machine and firmware architecture

Each state represents a specific operational condition of the device, defined by its suction_status variable. The states include fault handling, idle, transitioning to a surface, active operation, releasing suction, and fault clearing. The state transitions are dictated by real-time sensor readings and logical conditions, ensuring that Flex can respond dynamically to changes in its environment and maintain safety and reliability.

For example, in the "transition" state, Flex uses pressure readings to determine if a strong enough seal has been formed before transitioning to the "on surface" state. If the seal is inadequate or an unexpected event occurs, it moves to the "fault" state to disable the motor and start the vacuum pump. The app can read and set these states, meaning that the UI very closely represents the state of the device. This level of logic and interdependence between hardware components was necessary to meet the safety and usability requirements of our design.

A huge, huge thanks goes to Aadharsh and Baron, my team members, who really did make realizing Flex possible. While finishing the project in five weeks was taxing, the emphasis we put on polish and user experience made the end product really fulfilling.

Flex allowed me to me practice and learn new skills in all my favorite areas, and is arguably the most technically complex project I've worked on outside of FIRST. All of that made for an incredible experience that I'll never forget. I really believe the Flex concept has real merit as a product- and I hope to build a smaller, simpler V2 version at some point in the future.